With the coronavirus pandemic upending travel plans, you may find yourself daydreaming about your next holiday destination more than usual. If you’re fantasizing about hiking in the Andes, or having cocktails on a beach in the Mediterranean, it may be hard to wrap your head around the fact that some people would rather spend their next holiday at Chernobyl, Fukushima, or Auschwitz.

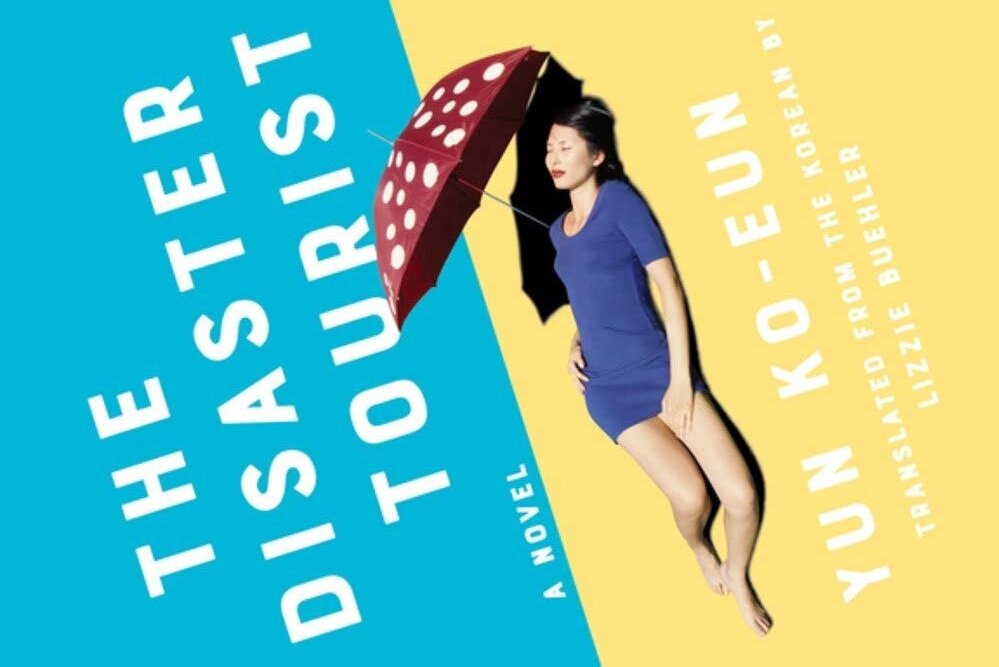

Yun Ko-eun’s novel The Disaster Tourist, the first of the Korean author’s works to be translated in English, is ostensibly about this very phenomenon: dark tourism. Yona, the novel’s protagonist, is a programming coordinator at Jungle, ‘a disaster travel agency’ based in Seoul, which specializes in travel packages to a roster of locations defined by disaster, big or small. In the book’s opening pages, Yona is planning a new itinerary to Jinhae, a city on South Korea’s southern coast, devastated by a tsunami. She adds a day of volunteering to the schedule to make it more appealing. (‘Voluntourism’—what critics describe as shallow, white-washing engagements with local communities—has been a growing sector of global travel for decades, after all.)

The Disaster Tourist is also a wry critique on the moral shortcomings of a gluttonous, pre-pandemic travel industry, with its absurd and costly, fine print and inhumane inflexibility. In the first chapter of the novel, Yona has to field a number of customer calls, including one from a client whose child is sick in the hospital—sorry, no refunds—and another whose travel companion passed away: ‘refunds are only possible in the case of the death of the purchaser’.

Yun Ko-eun’s to-the-point writing—and Lizzie Buehler’s brilliantly terse translation—show Jungle as a Kafka-esque work environment, where employees live in fear of committing a foul (an unspecified corporate faux-pas) that may lead to a yellow card (a largely arbitrary warning of lagging performance that may lead to irrelevance or even a demotion within the company). When Yona is repeatedly sexually harassed by her boss, she is advised not to say anything by a ‘friendly’ woman in HR, but is also encouraged to speak up by other sexual assault victims in the company, who tell her that ‘everyone knows’ about her ordeal, since there are cameras everywhere in the office.

Yona eventually hands in her resignation. But instead of accepting it, her boss (the harasser) offers her a corporate trip to one of the agency’s underperforming destinations: the island-nation of Mui. The trip is a perfect stick-as-carrot corporate bait: a week of labour disguised as a holiday. Yona’s task is to assess the quality of the program, and write a report about its viability.

Mui is one of those places that has suffered a disaster that isn’t considered devastating or grisly enough anymore for Jungle’s clientele. Its chief attractions are a desert sinkhole (that ‘didn’t really look scary anymore, or like anything special at all’) and a sixty-year old massacre event, when the native Kanu tribe ‘used farming tools to massacre [and behead] the Unda, a rival tribe. The manager of Belle Epoque, the only hotel resort on the island, pleads with Yona to save the Mui itinerary: ‘Since signing a contract with Jungle and building the resort, Mui has been tailoring everyday life to fit its role as a disaster zone…if disaster disappears from Mui, life disappears, too.’ His pleas make clear the predicament of many places on this planet—like my home country of Cyprus, also on the map of dark destinations—that have become inextricably dependent on tourism and foreign capital.

The Disaster Tourist’s plot unfolds as an existential, and at times horrifying, mise-en-abyme, where Yona’s role as a powerbroker on Mui is constantly undermined by a gnawing sense of her still being controlled by Jungle and its local affiliate Paul, an elusive conglomerate that controls everything on the island. The novel’s harrowing climax reveals that the island is so invested in its role as a resort for foreign travelers, that its native inhabitants are willing to sacrifice their lives for a place on the global tourist map. In the word’s of the hotel manager: ‘There’s not really a difference between dying in a natural disaster and starving to death, is there?’

The cannibalistic impulse at the heart of Jungle’s business model—only an extension of what real-life travel agencies offer, not an exaggeration—reflects a broader trend in contemporary society, which gobbles down sugar-coated versions of history in the form of entertainment, reducing the traumatic events of far-away places to social media-engineered wanderlust or high-grossing Netflix series. For a big part of at least the Western societies I have lived in, past events and historical figures are only as good as the amount of entertainment and spectacle they can provide to a contemporary audience with a rapidly declining concentration span.

There were moments in The Disaster Tourist where Yun Ko-eun could have given more; extending Yona’s insight further, revealing her backstory more fully. At the same time, the effect of Ko-eun’s withholding is undeniably powerful: like Kafka’s characters, Yona is as much an individual as she is a type, an every-woman of a twenty-first-century malaise defined by climate existentialism and solitary living in sprawling mega-cities such as Seoul. It is unclear whether Yona has always been a good fit for Jungle’s macabre, and cynical, business, or whether her ten years at the firm have turned her into someone that believes, wholeheartedly, that ‘disaster lay[s] dormant in every corner, like depression.’ Whatever the case, the result is the same: Yona is drawn, inexorably, towards a literal and metaphorical sinkhole, and Ko-eun’s novel treats Yona’s demise as a non-event; until, that is, her story is framed as tragedy and becomes the central focus of Jungle’s new Maui itinerary.

Dark tourism is human society’s basest voyeuristic instincts come to light. It highlights our attraction to raw spectacle and to the pornographic. It also confronts us with a human quality that is much more prevalent, and engrained, than we’ll admit, and which The Disaster Tourist captures perfectly: our often shocking lack of empathy.